|

RedSoxDiehard.com A Haven for the Diehard Sox Fan |

| ||

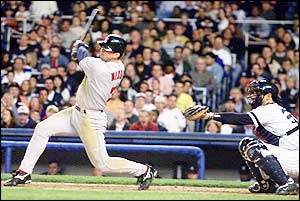

| Home > Departments > The Player Pages > Trot Nixon |

Born: April 11, 1974; Durham, NC Height: 6'2" Weight: 200

In 2001, Trot finally got the chance to be an everyday player, and he finally had the breakout year fans had been anticipating. With Carl Everett injured in June, Trot took over center field and settled into the 3-spot in the line-up. He finished the season with a .280 average, 27 home runs, 100 runs scored, and a gritty style of play that became one of the lone bright spots in an otherwise lost summer. Trot is the ultimate "Dirt Dog," giving his all on every play, even when the team is out of contention.

Once Trot took over the everyday right fielder role, he quickly became a fan favorite. And although he was injured for most of the 2004 season, he returned in September, just in time for some big postseason hits - like his three doubles in World Series game 4. More career stats from baseball-reference.com

• Trot Nixon graduated from New Hanover High School in Wilmington, NC, in 1993. He hit .519 with 12 HR and 56 RBI at the plate and was 12-0 with an 0.40 ERA as a pitcher, as his team went 26-1 and won the state championship. He was named High School Player of the Year by Baseball America. • He was selected in the first round of the 1993 draft by the Red Sox. He was the seventh player chosen overall in the draft. • Trot started the 1994 season in A Lynchburg, but was out for the season in July with a chipped bone in his back. • He began 1995 in Sarasota, where he reached base safely via a hit or a walk in his first 37 games. He was promoted to Trenton (AA) in August, but struggled there initially. • In 1996 Nixon played a full season in Trenton. He was called up to Boston when the rosters expanded in September. His major league debut was September 21, 1996, against the Yankees. He was used as a pinch runner in the 10th inning, picked up a stolen base, and played right field. His first plate appearance came eight days later on the last day of the season, during his first M.L. start. He singled in his first at-bat, and hit a double later in the game. • Trot spent the entire 1997 season with AAA Pawtucket, where he was named PawSox Defensive Player of the Year and Red Sox Minor League Player of the Year. • Trot spent 1998 in Pawtucket again, hitting .310, and was named Boston's Minor League Player of the Year. He was called up to the majors in September, where he made four starts in right field and one in left. He was put on the postseason roster, and started the deciding Game 4 of the Division Series at Fenway Park. He went 1-3 with a walk. • Trot Nixon was Boston's Opening Day right fielder in 1999. He hit his first M.L. home run April 8 in Kansas City. Trot struggled early in the season, but hit .393 in July and .298 after the All-Star break, to finish the season at .270. He had a 3-homer game in Detroit in July, making him only the fourth Red Sox rookie in history to accomplish that feat. Along with Brian Daubach, Trot was named Red Sox co-Rookie of the Year. • In the 2004 World Series, Trot had an RBI single in Game 3, giving the Sox a 2-0 lead. In Game 4, he had three doubles. His third-inning double was hit on a 3-0 count with the bases loaded, and almost left the park. It hit off the outfield fence and scored two runs, giving the Sox some breathing room with a 3-0 lead in the game.

Father aided his drive to succeed By Bob Duffy, Globe Staff, 5/30/00 He saw the ball.

Everyone else at Fenway Park last Wednesday night saw the broader tableau: a foul fly by Toronto's Marty Cordova drifting obviously out of play, behind the concrete right-field grandstand, into the bank of cast-iron seats, out of reach except to civilians.

So for a moment, he would recall, he was no longer the Sox' second-year right fielder, he was again a blood-and-guts quarterback at New Hanover High in Wilmington, N.C. He hurdled the wall and the first few rows as if they constituted a goal-line defense. He vanished into the mass of flesh and concrete and cast-iron, out of sight for almost a minute.

When he reemerged, he had two red welts atop his chest. He did not have the ball, which had glanced off his glove as he crashed into a seat, and he was fortunate he still had all his body parts. But he did not have a choice on the play, either, he would say after his second single had set the stage for a winning, 11th-inning home run by Brian Daubach and resuscitation for the Red Sox. Perhaps it had looked foolhardy, he acknowledged, ''but I really thought I had a bead on the ball.''

So there was no alternative but to ignore the hazards.

Just as his father taught him.

His ninth-inning home run Sunday night made him an instant part of Red Sox lore. The two-run shot into the right-field seats at Yankee Stadium settled an epochal pitching duel between Boston aces past (Roger Clemens) and present (Pedro Martinez). It provided the Sox with a 2-0 victory, gave them the rubber game in the three-game summit with the two-time defending world champions, and restored Boston's one-game American League East edge on New York. And it enabled the Sox to savor their Memorial Day respite as they awaited tonight's opener of a Fenway series against the Royals.

Beyond that, it served as an emphatic riposte to what Nixon perceived as trash talking by Clemens, who shouted at him scornfully when the Boston batter cast a dubious glance after being called out on strikes in the first inning.

''Whether he respects me or not, that's fine,'' Nixon said. ''I have to earn my respect.''

He earned fame with his prime-time blast. But the respect he craves - and which Clemens ignored at his own peril - had been achieved with plays like his mosh pit dive against Toronto, not to mention his seventh-inning one-hopper to the 399-foot sign against Clemens, an easy double that Nixon turned into an unlikely triple with a nonstop dash around second and a headfirst slide into third.

Those are the calling cards of Nixon the player. The flashy statistics - his .323 average, 6 homers, and 29 RBIs - are window dressing. He conducts himself with the intensity of an inferno, as if he were back running the New Hanover veer offense as a quarterback who, in his words, ''would find a way to win, who wouldn't put up the greatest numbers in the world, but `W' is the greatest letter of them all.''

At 26, Nixon realizes that once-a-week gridiron fury must be tempered somewhat in the daily grind of baseball, because ''you can't go up to the plate mad at the world. I want to be an intense player but not play out of control.''

It is an approach that certainly has impressed his manager, Jimy Williams, who saw enough fire in Nixon that he declined to send the rookie back to the minors last season even after he got off to an .061 start at the plate in April.

''He's a tough kid,'' says Williams. ''Whether he played football or whatever, I think it's how you're raised that has a lot to do with it: a parent or coach [instilling] that mental toughness.''

Williams may not be a child psychologist, but he has pinpointed the source of his right fielder's development. In Nixon's case, the compelling force was his father.

William Nixon was a North Carolina farmboy ''who learned through trials and tribulations, I'm sure,'' says Trot. The elder Nixon grew up hard and turned himself into a success. He played football and baseball at Atlantic Christian (now Barton) College in Greenville, N.C., received offers to play minor league baseball, but opted to attend medical school and became a surgeon.

His passion for sports never abated, and Trot, the third of his four children, became his instrument of competition.

''My father's always pushed me to the limit and maybe a little bit further all the time,'' says Trot. ''He knew what buttons to push, how to get me fired up. That's probably what made me into the player I want to be.''

That player became a first-round Red Sox draft choice, the seventh pick overall in 1993, and a quarterback who attracted many scholarship offers. In fact, he was on campus at North Carolina State, ready to begin his college football tutorial, when the Red Sox signed him at the deadline in 1993.

While he loved football, and still does, Nixon saw limited horizons in the sport: ''Maybe if I had progressed over the years, I could have a chance to do something. Maybe all-conference ... maybe All-America.'' But the NFL was not viable; major league baseball was.

And his father drove him. William Nixon was a taskmaster, with a farmhand's work ethic and demand for devotion to the cause. He would throw endless batting practice to his son.

''He hit me [with pitches] a few times because I didn't have my mind set the way I should have,'' says Trot. ''I'd turn the corner and then, all of a sudden, I was concentrating on what I was doing.''

There was no letting up. ''If I played poorly or it looked like I was a little intimidated,'' says Trot, his father would preach ''just a relentless type of attitude.''

But William Nixon was not the stereotypical autocratic athletic parent. When Trot was 11 or 12, he remembers, his father called him into his office and said, ''Either I can push you or I can let you go down your own path.''

The option was Trot's, and ''I decided to be pushed.''

Then there was no retreating, even if he occasionally bristled at his father's instruction.

Deep down, he wasn't looking for escape, anyway. ''I think that was just [his father's] way of molding me,'' Nixon says. ''It was tough. But it all paid off in the end.''

And as the son progressed, the occasionally prickly relationship thawed. ''I think it's gotten closer over the years,'' says Nixon. ''Probably when I was younger, it was probably more competitive. The older I got, I got a little better. He started enjoying it more.''

Nixon credits his success in part to his high school coaches, Dave Brewster in baseball and Joe Miller in football, who picked up where his father left off; Williams for working with him during his bleak beginning after five years in the minors; his Boston teammates for encouraging and guiding him in the midst of his struggles; and hitting coach Jim Rice, third base coach Wendell Kim, pitching coach Joe Kerrigan, and bullpen catcher Dana LeVangie for their tireless instruction.

The one thing they didn't have to teach was a will to endure. His abandon, Nixon believes, stems from ''just the fact that I want to win so bad.''

Now where in the world could that have come from?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home • Departments • Features • Archives • More Info • Interact • Search | ||||

|